When a new Assassin’s Creed comes out, a lot of people use the phrase ‘open-world fatigue’ to express their exhaustion at what they feel is an endless stream of dull and massive spaces with very little to do other than the same old chores they’ve been doing for years.

I get this. The special open worlds we’ve been given recently require a certain level of dedication in the first place, and the boring ones are just brain wallpaper. For the former, Red Dead Redemption 2 or Breath of the Wild are good examples of open worlds that seem to reinvigorate the genre in their own unique ways. For the brain wallpaper, I put forward anything formulaic by Ubisoft.

Side-note time: I love formulaic Ubisoft games. Assassin’s Creed is great fun (I’ve literally hundred-percented four games in the series for some reason). But we’ve been playing similar enough variations on their formula since at least 2011, if not earlier. Brain wallpaper is good sometimes! Sometimes you just need to chill out and do some virtual murder and y’know what? That’s okay.

Red Dead Redemption 2 goes about open worlds in an incredibly luxurious, almost romantic way, while Breath of the Wild goes about it in a mathematical way, like an abacus-laden desk-haver, like it pushes its glasses up with the bottom of its pen while writing out formulas to do with triangles.

The romance of RDR2 comes from its beauty and simplicity. This space has to feel very real, so there are two main things Rockstar has to do. First up is the obvious bit: graphics. The graphics in RDR2 will still be impressive in a decade, because there’s wonderful attention to detail in everything, making this space feel ripe to homestead in. (There’s also a side-thought about how characters’ feet interact with surfaces that I could get into, but probably best I don’t).

Second is making living things feel real. Animals may not have to talk, but animating them and making them interact with the player and the world properly probably takes unholy amounts of time. Then humans have the issue of facial expressions and dialogue lines that properly match up to the player’s actions in the world. How do you make an NPC react properly when the player blows themself up with dynamite, falls off a train bridge, and loses their hat in a waterfall? I’d probably make them say “oh lordy”, but that’s just me.

Well whatever, making a world like RDR2’s takes a long time. Same for Breath of the Wild. When I was talking about triangles earlier I wasn’t just being annoying. As summarised by Robert Yang, when people first played BotW they weren’t enjoying it, either feeling over-guided to their destination or too lost when exploring. Crafting this open-world took trial and error on Nintendo’s part.

They started implementing triangles. If you see a triangle it blocks your view. You can either go around it or get on top of it to see what’s next. What if when you went around it there were enemies to fight, or when you got to the top there was a little collectable? Oh, and by the time you get a better look at what’s behind it, what if there were seven new things to look at, whether it’s a glowing shrine, a strangely-shaped mountain, or just a cool-looking patch of snow? Read that summary above as it’s better than I can do, but either way, doing that stuff takes time.

But you know what clearly takes less time? Making Xenoblade games. We have had two new Xenoblade games since BotW came out and zero new Zelda games. Xenoblade has also offered two chunky bits of DLC that feel like standalone games and suck up around 30 hours each. So, is Monolith Soft’s dev cycle just as slick and formulaic as Ubisoft’s?

Well, by the looks of it, yeah. These spaces don’t really do much in terms of interacting with the player or convincing them that they’re real spaces. They have icons and destinations. They have objects littered on the ground to collect. They don’t go for the luxuriousness of a Red Dead or the fine-tuned magic of a Breath of the Wild. They’re kinda just big spaces to hang out in.

So, why am I not tired of them? Well, I do like their bonkers stories, but that can’t be all there is, right? Otherwise, I’d prefer 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim for letting me just experience a bonkers story (or I’d just watch the tele). Well, the combat’s pretty good too, but that’s true of a lot of games that suffer from dull open worlds. I know a lot of people don’t like it, but shooting a gun in Cyberpunk 2077 feels good.

Nope, I think the true magic trick of Xenoblade is that everything is just bloody massive. You look one way and there’s a big gorilla, another way and there’s a giant grassy plain that takes a decade to cross, another and there’s some tall thing that you want to be on top of. This isn’t the same as BotW–most treats are telegraphed rather than suggested. Instead, it’s just pretty darn cool.

I wasn’t cool enough to boot up the original Xenoblade Chronicles on the Wii. I only played it after I played Xenoblade Chronicles 2. But I imagine the main hook for people getting into that game was the scale of it all (as well as the excellent music but let’s ignore that for now because it doesn’t help me make my point).

Just the feeling of insignificance that a giant creature a million levels higher than you gives to the player is something uniquely old-fashioned. When Xenoblade Chronicles 2 came out, people complained that you could get ruined by a level 81 Territorial Rotbart in the opening area, which I understand, but the fact that the game did it at all is weird and exciting.

This sense of scale has been utilised elsewhere, most notably by Team Ico. Shadow of the Colossus is an excellent example of scale offering a feeling of insignificance, making the player feel like they’re fighting against unbelievable odds. I think Monster Hunter does this really well too; when you first get trampled by a Rathalos and the big beast just stumbles to the ground, that’s pretty terrifying, hilarious, and magical.

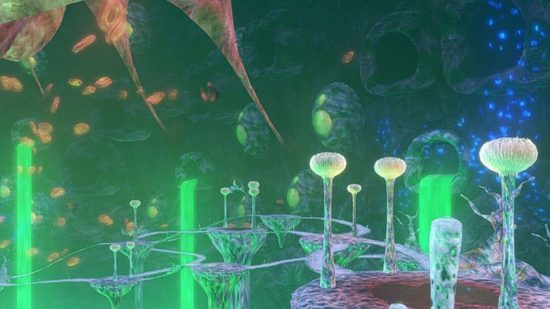

Xenoblade’s art direction, particularly in the second mainline game, helps the loud bigness of everything come across. Colours are big and bright, monsters are uniquely shaped, and everything has a general sense of wonder. Just the conceits of these spaces–the backs of giant titans, the body of a massive mech–are enough to spark the imagination.

Side-note round two: I think this is why some Assassin’s Creed games can get their hooks in me more than others. Renaissance Italy is objectively cooler than the American Revolution. Assassin’s Creed Odyssey is cool because I want to go to Greece. Digital historical tourism is the key here, but it only works if you’re actually interested in the place.

One thing this helps with is making Xenoblade’s interiors feel even more special than they already are. The spaces they construct for these games are just so excellently big and detailed, offering winding paths up and down and in and out. Everything leads back to where it ought to. Everything is as big as it should be when looked at from the outside. It’s beautiful.

The beauty of the music helps too, of course, but it also lines up with the series’ philosophy of bigness. How often does Assassin’s Creed just have a spiky guitar solo come in the middle of grand choral chants or driving strings? They should do it. It just makes everything more fun, especially when you’re going to be stuck there for dozens of hours.

Yasunori Mitsuda’s work on the Chrono series is legendary, and it brings a similarly hefty stamp to mark all the Xeno games, too. There isn’t any shyness in the loudness that Xenoblade brings, whether it’s aural or visual, which helps everything feel special. It may be some sort of style-over-substance mind trick, but it works on me.

So, how does Xenoblade sidestep open-world fatigue? By being big, loud, and confident to create a world that makes the player feel insignificant and special at the same time. It doesn’t have the beauty of a Red Dead, nor the mathematical mind of a Breath of the Wild, but it has my heart in spite of that.

To see our thoughts on the latest entry, check out our Xenoblade Chronicles 3 review. For more, take a look at our Xenoblade Chronicles 3 characters, Xenoblade Chronicles 3 heroes, and Xenoblade Chronicles timeline guide for more.