I like to see a familiar setting reinterpreted in different art styles. Rachel Harrison’s Warhammer 40,000 novel Blood Rite was once released as a Japanese light novel complete with bishi illustrations of Sanguinius and Astorath the Grim (opens in new tab), and that made me want an entire 40K manga drawn in the same style. So I don’t mind when 40K games look like they take their art cues from unexpected places, whether webcomics and Flash games like Shootas, Blood & Teef, or the sprites of ’90s shooters like Boltgun.

Still, there’s something to be said for fidelity. The 40K universe is famously the origin of the phrase “grim darkness”, a place that’s gothic, baroque, industrial, and heavy metal all at once, as typified by John Blanche’s artwork (opens in new tab). And Darktide has fidelity to that, all the way up to its purple Cadian eyeballs.

The universe is a big place, and whatever happens, you will not be missed

I should explain. In 40K, Cadia’s an Imperial planet on the edge of a giant hole in reality called the Eye of Terror, leading directly to the daemonverse of Warpspace. The humans who settled there developed violet eyes, probably as a result of being borrow-the-sugar neighbours with the reality-warping Eye of Terror. Cadia was the first line of defense against invasions from Warpspace and survived multiple incursions before eventually falling, though only after a heroic final stand by its Astra Militarum troops. In Darktide’s character creator, the option to have purple eyes is locked unless you chose Cadia as your birth world, and if you play a Veteran as well you’ll reference Cadia’s fall in dialogue.

The previous watermark for fidelity in a 40K game was probably Space Marine. There’s a moment in Relic’s third-person murder ballet where you, an eight-foot-tall transhuman warrior, walk through an infirmary full of ordinary Imperial Guard soldiers. One of them repeats the Imperial mantra “Only in death does duty end” while another screams he can’t feel his legs, and as you pass a third reverentially sighs, “I got to see a space marine before the end.” It’s bleak, but at the same time it makes you feel like a giant. Hours later, you arrive at a factory where Titan Invictus, a mech that’s about 108-feet tall and capable of winning wars by itself, is being stored. Suddenly, you feel tiny.

Scale is important to 40K, a setting that looks at other science-fiction’s robots, guns, spaceships, and population numbers, then says, “We could make all that bigger.” The Imperium boasts a million worlds and its hive cities have populations in the billions. You get a sense of that in Darktide when you break out of the cramped corridors of hab blocks that used to be people’s homes and look up to see Tertium Hive soaring beyond the edge of the draw distance. Or in the level where you protect a train in a consignment yard, from which you can see a voidship under construction. A craft that’s miles long and will need thousands of souls to crew it, dangling from the ceiling by chains.

It’s common enough for science fiction to point out space is big, but 40K really leans into the feeling of insignificance that comes with that. When there are so many people spread across so many worlds, our modern ideas about individualism must seem laughable. In a world like this, believing one person matters is like believing in feudalism today. The Inquisition responds to a world under threat, in a system where decent military forces are distant—the best of the local regiments, the Moebian Sixth (opens in new tab), have turned traitor and become the relatively well-armed Scab enemies—by throwing “rejects” like you at the problem.

We’re disposable, because of course we are. How could the machinery of the Imperium look at the billions and billions of people it has and see the unique individuals? What it sees is a resource that’s practically limitless. The metal produced on Atoma Prime, which makes the somewhat-better-than-average tanks that loom over Darktide’s maps, is worth valuing and protecting. We’re not.

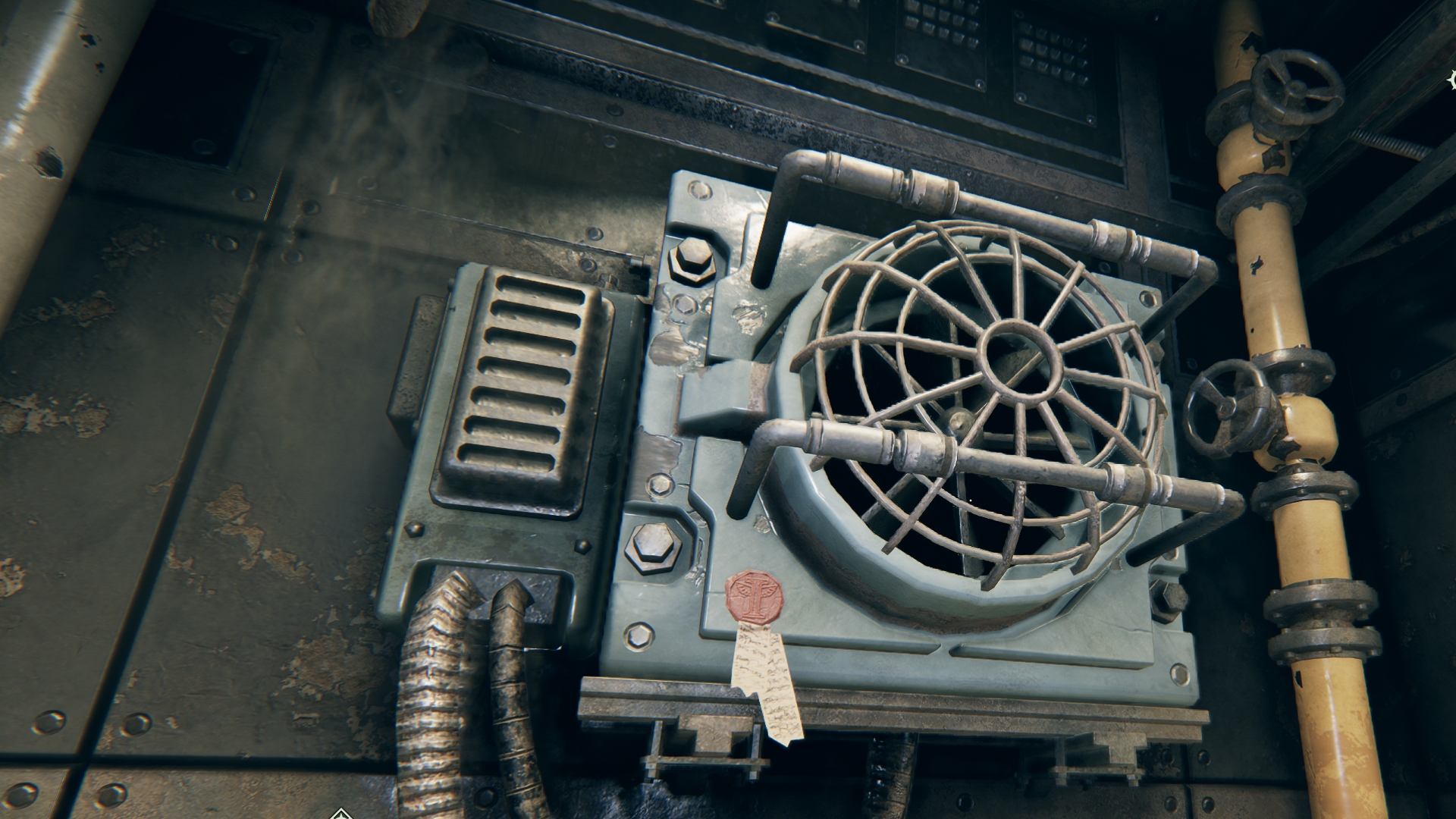

So Darktide gets that right. But the Catachan Devil is in the Catachan details, and Darktide gets them right too—from the moment in the prologue where you see paper attached to an airconditioning unit by a wax seal, as if there’s an inspector out there checking the machinery and leaving notes on parchment. It gets the juxtaposition of modern industrial and sacred antiquity spot on. A medieval church blares propaganda from loudspeakers; the spaceship’s windows belong in a cathedral; the equivalent of a server farm is a “servitor array” that turns out to be an ossuary (opens in new tab) with skulls and ribs piled to the ceiling.

The grimness is there too, in the haggard faces that are the only options available (I’ve never seen a character creator so averse to letting you look pretty), and the scuffed weapons that have all clearly been used for years, probably by people who died holding them. But it’s also contrasted with the conversations between the Rejects, who make fun of the Zealot’s singing, refer to Lord Commander Roboute Guilliman (opens in new tab) as “big fella”, and gossip about the Inquisitor’s crew. They joke and bond and share stories. The Imperium may not see them as individuals, but we do. It’s a huge and awful place, but the little details matter, just like the little people do.

I hope Space Marine 2 manages to do that as well as Darktide and the original Space Marine did. I think it might. The reveal trailer (opens in new tab) references the infirmary scene from the original game, with three marines leaping down from the sky to save a group of Imperial Guard soldiers in the courtyard of a ruined cathedral. The marines’ armored feet leave cracks in the stone, the camera pans up them like statues of saints, and a surviving soldier sees them and whispers, “His angels,” with wonder in his eyes.

His purple eyes.