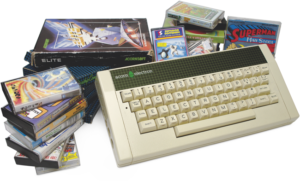

Year Released: 1983

Original Price: £199

Buy It Now For: £20+

Associated magazines: Electron User, Micro User, Acorn User, A&B Computing, Acorn Programs

Why The Acorn Electron Was Great: The Electron offered the main functionality of the BBC B at half the size, and at a fraction of the cost. It had strong software backing, and boasted one of the best keyboards of any computer, with great feel and responsiveness and a variety of shortcuts to common BASIC commands. And it was built to last, too.

After the roaring success of the BBC Microcomputer, Acorn was a company going places. It had conquered the schools market almost unchallenged, and with a cheaper, cut-down sibling to the Beeb designed for home use on the way, it was massively confident that it could dominate the marketplace. Four months ahead of the Electron’s launch, joint managing director of the company Chris Curry was in bullish mood. “We are not placing any limits on the size we can grow to,” he told The Times. “We see the Electron as a very powerful threat to the existing dominance by Sinclair and the Commodore VIC-20. We hope to get half the home computer market.”

“It was absolutely manic – an insane time really,” recalls Tom Hohenberg, Acorn’s former marketing manager. “There were exhibitions going on all the time, and there’d be 50,000 to 60,000 people besieging the stands. The BBC Micro was selling like hot cakes – we couldn’t make them quickly enough – so there were huge hopes for the Electron. Half the size, half the price, and the same sort of power. We were buzzing.”

Lessons had clearly been learnt from the supply problems that had beset the BBC. Thankfully, due to the machine’s tie-in with the broadcaster, the Beeb still went on to become very successful. Six months ahead of the Electron’s launch, Curry told The Guardian that the new model would not even be advertised, let alone sold, until they were “completely confident that stocks are available”. “More than almost anybody else we have suffered in the past from problems of lack of product when the demand is high,” he said. “We are not going to let it happen again.”

An expanded Acron Electron (img: John Simpson).

Launch day arrived on 23 August 1983, and anticipation was massive. The first review of the new machine was in, and so glowing that Acorn quoted it extensively on the full-page advertising it took out in the newspapers. “Compared to other micros in its price range, the likes of the Spectrum, Oric and VIC-20, the Electron wins on all counts,” What Micro? magazine said. “It has better graphics, a better keyboard, and faster and more versatile BASIC. Acorn had better be ready for a rush, there’s going to be one.” If only Acorn had paid closer attention to that last line.

Acorn’s strategy was to show parents that the Electron was a way of bringing their learning at school on the BBC into the home, and a £300,000 TV ad was commissioned to make the point. “It took three days to shoot, and was quite an epic production,” says Hohenberg. “There were lots of kids and several sets. We spent £3 million on airtime.” The marketing of the machine was so successful that a reported 300,000 orders were received for the run-up to Christmas 1983.

Significantly reduced in size from its predecessor, but lacking some of the features and connectivity, the Electron’s dimensions had in fact been based on a tissue box, after Acorn found itself unhappy with the case put forward by an industrial designer. “It will have been six to nine months to do the basic design, but then there were problems with the ULA,” says former Acorn hardware designer Steve Furber. “We were geared up to produce 300,000,” continues Hohenberg, “and then the ULA, the heart of the machine… only one in ten of them worked.”

Electron User was a popular mag of the time.

As a result, only 30,000 Electrons hit the shelves in this period. “All these families had promised the kids an Electron for Christmas, and it just wasn’t obtainable,” says Hohenberg. “We’d get a shipment in, then there’d be a stampede. People were fighting in Rumbelows.” The Manchester branch of WHSmith reportedly received 1,500 phone enquiries in one week alone from people desperate to find one in time for Christmas.

Despite the production problems, support for the Electron steadily grew. Acorn’s software arm – Acornsoft – led the charge, and its first batch of games included some superb conversions: Snapper (an excellent Pac-Man clone), Meteors (Asteroids) and Monsters (Space Panic), as well as Peter Irvin’s fine space-based shooter Starship Command. “I sent it to several publishers who all wanted it,” he explains. “But I decided to go with Acornsoft because, although their royalty rates were lower, I thought they were the better publisher.”

The other main player on the Electron software scene in the early days was Leeds-based Micro Power. Fine conversions of Frogger and Donkey Kong – Croaker and Killer Gorilla – sold well, but the real gem was the outstanding maze-based shooter Cybertron Mission, heavily influenced by Berzerk. Alongside the early software players came the arrival of Electron User, the only magazine dedicated solely to the Electron. Launched in September 1983, it became vital to the machine’s user base.

Inside the Acorn Electron. (image: Steve Furber).

Late 1983 also saw the first Electron offerings from Superior Software, a company that would become the most important and long-lasting supporter of the machine. Already active on the BBC scene, Richard Hanson’s company was wary of Acorn’s supply problems, but dipped a toe into the market anyway. “Richard spent half the night reprogramming a one-armed bandit simulator,” says ex-Superior man Steve Botterill. “Beeb sales were brilliant, but it took until the end of the year before Electron sales picked up.

We had put about half-a-dozen titles together for it to see how it would go.” After small numbers were initially picked up in the countdown to Christmas, Superior Software’s big break for the Electron arrived. “In February, WHSmith ordered 1,000 each of seven Electron titles,” Botterill recalls. “This marked the start of the Electron selling big numbers.”

By February, a backlog of 200,000 orders for the Electron itself reportedly still remained. Acorn’s production troubles soon eased, but the missed Christmas rush resulted in tens of thousands of machines arriving into the country with only a fraction of the demand for the machine remaining. “We had this warehouse in Wellingborough,” Hohenberg recalls. “Before Christmas, the trucks were lining up at one end wanting to take the few Electrons we had away to stores, but now the trucks were all at the other end, delivering, and the market had completely dried up. Seeing Electrons piled floor to ceiling… it was very depressing.”

And the company’s troubles didn’t end there. Shortly after the Electron’s launch, Acorn had attempted to capitalise on its expected success by advertising 11.23 million shares for trading on the London Stock Exchange. The company’s performance in the market was soon described in The Times, however, as “abysmal”. Coupled with ill-fated attempts to set up operations in the USA and Germany, from a position of enormous financial strength, the company soon found itself in serious difficulty. Even Acorn’s much-prized contract with the BBC was said to be under threat.

Like many 8-bit computers of the time, the Electron sported an add-on

cassette deck. (Image: John Simpson).

The software market for the Electron was gaining in strength, however. 1984 saw the arrival of Acornsoft’s classic Elite. “The Electron version was more restricted than the BBC disk edition,” says David Braben. “The video hardware on the Electron was very poor compared to the BBC, and we couldn’t do some of the trickery we did on the BBC to save memory – this is why it was black and white on the Electron.” Even in cut-down form, Electron Elite remains one of the finest technical achievements on the machine, and although Braben wasn’t overly happy with the version, he and co-author Ian Bell have left one lucky user a present: “We never bought an Electron – one was loaned to us by Acorn, and when we finished, we attached a note to the inside of the case, saying ‘Elite was written on this machine’,” he says. “We both signed it, so somewhere, hopefully, it’s still there in someone’s machine.”

Other 1984 arrivals included A&F’s Chuckie Egg, as well as the evergreen (literally) Repton. This Boulder Dash-influenced series was Superior’s biggest seller, and loomed over the 8-bit Acorn scene throughout the Electron’s life. Acorn’s popular Plus 1 and Plus 3 expansion boxes were launched too, between them adding joystick and disk-drive interfaces, as well as ROM cartridge slots.

Doubtless spurred on by the steadily increasing user base, Acorn seemingly rallied. The BBC contract was renewed, and by September sales of the Electron were said to be over 90,000. A stronger than expected Christmas saw this number double, with a Dixons spokesman expressing delight that the Electron was selling “four to five times as well as we had expected”. This in spite of Acorn sticking to its £199 launch price, the same price as the heavily discounted C64, and vastly more expensive than the all-conquering £129.99 Spectrum 48K. In January 1985, however, Sir Clive Sinclair put the squeeze on still further, slashing the price of the Spectrum+ to £129.99. Acorn responded immediately, dropping the Electron by £70 to go head-to-head at that price point, but the new mark undoubtedly put further pressure on the company – the Electron was widely known to be costlier to produce than the Spectrum.

Despite strong Christmas sales, the company suspended share trading five weeks into the new year after its share price dropped to 28p, down from a high of 193p the previous year. Redundancies followed, and Olivetti stepped in to mop up a cut-price 49.3 per cent stake in the company, increased to a massive 79.8 per cent a few months later. After recording a £10.8 million profit in 1984, Acorn was now reeling from a £22.2 million loss. “That was grim,” says Hohenberg. “We just felt like ‘oh my god – we’ve sold out to big brother’.” Olivetti chairman Carlo De Benedetti criticised the company in an interview with The Times, observing that it’d tried to move into the US market “with forces totally inconsistent with their size, and their financial and managerial strength”. A loss-making sub-£100 price tag was soon placed on the Electron, with the bulk of Acorn’s warehoused stock ‘distress sold’ to Dixons. Profits were no longer an issue – Acorn needed cash, and fast.

Four Great Acorn Electron Games

Read the full feature in Retro Gamer issue 57, on sale digitally from GreatDigitalMags.com

Retro Gamer magazine and bookazines are available in print from ImagineShop