Pasokon Retro is our regular look back at the early years of Japanese PC gaming, encompassing everything from specialist ’80s computers to the happy days of Windows XP.

Astarion, Gale, Shadowheart, and Lae’zel have just infiltrated a goblin camp not too far outside a peaceful settlement filled with people to chat with, optionally recruit, and take quests from. And after some cautious wandering and a little light-fingered pilfering the party has finally found the dark elf and their goblin underlings lurking within. It’s at this point the game switches to a turn-based battle system, and careful tactical movement and wild spell flinging eventually win the day and earn our band of heroes their well-deserved rewards.

This is not Baldur’s Gate 3.

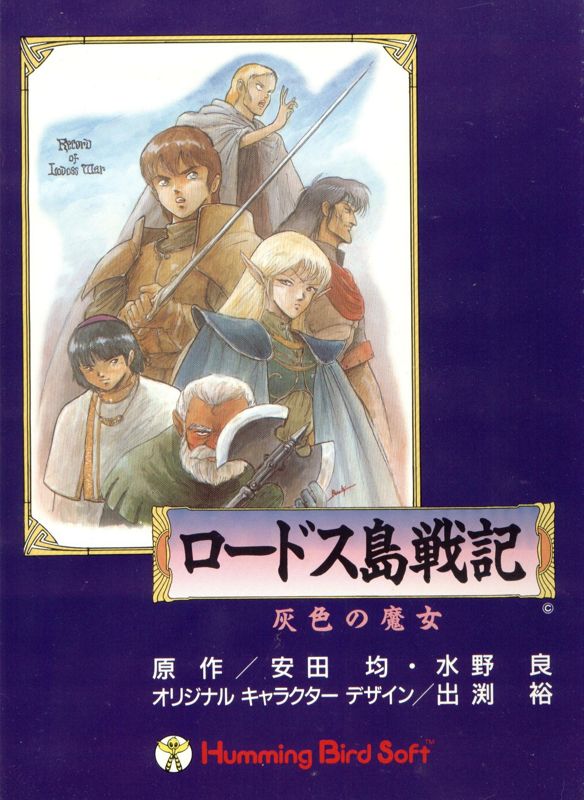

It sure sounds like Baldur’s Gate 3, but this is all playing out in Record of Lodoss War: Haiiro no Majo, an RPG released on most major Japanese computers from the late ’80s to the early ’90s. Like the Lodoss books it’s based on, this game freely takes from the Dungeons & Dragons setting it clearly adores. It emphasises giving me an adventure of my very own rather than forcing me to use the characters from the book and famous anime series.

All of the usual faces like Parn and Deedlit (who got her own Metroidvania just a few years ago) are still in here of course, sitting in various town taverns and just itching to join my team if I speak to them, but I’m under no obligation to accept their offers. Haiiro no Majo expects me to create a full team of up to six custom heroes before my own story can even begin, hence the Baldur’s Gate crew making up my party.

The process of creating these characters reminded me of the many happy hours I once spent with another Dungeon & Dragons classic: Eye of the Beholder. Having to pick between humans, elves, dwarves, and all the rest, then hoping their randomised stats are capable of supporting the sort of class I had in mind for them—it’s all part of the fun. Unlike Westwood’s later legendary dungeon crawler I can only lightly tweak the randomised stats I roll here, but this slight limit on customisation leads to a sprinkling of extra roleplaying in the long run.

Maybe my warrior hits like a tank but has all the endurance of a wet paper towel; maybe a wizard who isn’t the best spellcaster in the world but seems to dodge everything thrown at them opens up a fun new way to play.

The small dungeons scattered throughout the land are all presented as first-person mazes to explore and fight in. In my case they’re also home to a lot of swearing at illusory walls and trapped chests waiting in the torchlit gloom. Using graph paper to map them out is very much recommended.

At least the battles within only occur in fixed (although invisible) spots, which makes poking around feel like honest investigation rather than a tedious fight to reach the nearest door without being assaulted by kobolds again. Clearly the flat square arenas Lodoss uses for these scraps can’t compete with the freeform multi-level majesty of Larian’s latest RPG, but they were trying just as hard to recreate the same tabletop feel 30 years ago. I still need to identify the biggest threats and then close the distance between my party and them quickly but carefully, and I have to ensure my toughest characters stand between any axe-wielding menaces and my squishier spellcasters.

It may look simple, but this sort of play is as engrossing here as it is anywhere else. I still cheer when my favourite damage dealer carves a path through the battlefield or my healer risks it all to save the day.

Lodoss’ love for roleplaying—true roleplaying with friends, arguments about who carelessly blundered into the traps this time, and striking out into the unknown just because I can—really shows in the freedom it gives me to handle problems in my own way (if I even want to bother with these problems at all). So many RPGs from this early era of gaming have to severely compromise in one way or another: 1987’s Dungeon Master handled the interior exploration side of things perfectly, but at the expense of ignoring the entire world around it and everyone who might have lived in it.

Final Fantasy, released the same year, kept the continents and characters but streamlined the rest of the genre’s delights down to the bone. Ultima V gave us a static Britannia and a hideous interface that still sets my teeth on edge. Lodoss, remarkably for being 30 years old, feels like the complete, unaltered-as-possible pen-and-paper package, spread across just a few floppy disks.

I’m allowed to wander anywhere my party’s legs can carry them, whether that’s through expansive overland forests or deep multi-layered dungeons, and that means just how much trouble they get into, and how prepared they are for it, is almost entirely up to me (or entirely my fault). Political alliances formed, people met, and quests completed or ignored in one part of the map actually have a direct impact on the rest of the island.

So while it might be a good idea to do a particular quest while I’m here, I don’t have to. I don’t have to use a balanced team. I don’t have to stay in this town and solve whatever problem the locals are having if I don’t want to. I don’t have to keep out of enemy territory. I don’t have to check a new piece of equipment to see if it’s cursed before I make someone wear it. Oops.

It’s this opportunity to do exactly as I please, even if doing as I please lands me in a whole heap of trouble, that makes the game so true to Lodoss’ tabletop origins I can almost hear the shuffling of character sheets—even when I’m busy trying to shoehorn Baldur’s Gate’s explosive boot-eating wizard, literally hot tiefling, and sassy healer into it.

My “Gale” here’s spellcasting will inevitably either utterly decimate enemies in a single shot or completely miss—yep, that’s the wizard of Waterdeep alright. “Karlach’s” broad movement range makes it easy for her to rush in and give anything standing nearby a nasty whack. And I really do tend to last longer when I remember to have “Shadowheart” hang back and cast Bless.

It may just be some stats and the game’s relaxed nature combining to give my imagination the room to spin these choices and interactions into something more than they really are, but if that’s not the one true indicator of great roleplaying—the sort of experience Lodoss has always strived to recreate—then what is?